In the Doghouse

Synthetic Alcohol's Pint of Utopia Masks Liters of Warning Signs

is no such thing as a free three-martini lunch. That, however, is the goal of a new strain of lab-made liquor, termed “Alcosynth,” according to a report published by according to a report published by Drink Sector, an industry analysis firm. Alcosynth creator Dr. David Nutt claims the drug has all the pleasant inebriation of alcohol without the hangover—or the physiological damage from long-term use. It almost seems to good to be true.

is no such thing as a free three-martini lunch. That, however, is the goal of a new strain of lab-made liquor, termed “Alcosynth,” according to a report published by according to a report published by Drink Sector, an industry analysis firm. Alcosynth creator Dr. David Nutt claims the drug has all the pleasant inebriation of alcohol without the hangover—or the physiological damage from long-term use. It almost seems to good to be true.

In fact, any ability to test or rebut Dr. Nutt's claim runs afoul of his lab's reluctance to share any details of the compound, citing pending patent applications. But there are some basic problems with the idea that an alcohol-without-drawbacks is a reasonable goal. Certainly, it would be better and more humane if those who engage in dangerous levels of drinking were less likely to suffer for their decisions. The problem is, those decisions still carry substantial risks that alcosynth does not seem able to rectify.

First and last, the goal for the drug is to mimic the acute intoxication of alcohol. It is important to note that hangovers and chronic liver disease are the results of heavy use, and by setting its sights on those symptoms, alcosynth explicitly lauds those patterns and turns a blind eye to the fact that patterns of overdrinking are as much deliberate creations of the alcohol industry as they are personal choices. Even if the physiological damage is avoided, using a "safe alcohol" at levels that would otherwise cause a hangover puts into play all of the compromised decision-making—including hazardous driving, violence, risky sexual behavior, and vulnerability to crime. Moreover, as LiveScience reports, nothing at all is known about whether alcosynth can cause dependency, nor whether the physical withdrawal symptoms would approximate alcohol's.

Dr. Nutt told the BBC that he had previously experimented with benzodiazepines, but now says he has moved on from there to other drug classes. This raises a very real specter: of alcosynth not replacing alcohol, but being combined with it. Many non-alcohol psychoactive drugs whose effects overlap with those of booze—including benzodiazepines (Valium, Xanax, Klonopin) and GHB—have disastrous effects when combined with alcohol. These effects include blackouts and incapacitation, leading some to gain a reputation as "date rape drugs". This is not to say that alcosynth will be inevitably used for this purpose; rather, it's to suggest that an unregulated sibling drug to alcohol leaves plenty of room for misuse and abuse.

The idea that the physical harms from a dangerous drug can be totally evaded through unrestricted sale of a rival drug is quite au currant. As Dr. Scott Edwards, an addiction specialist at Louisiana State University Health Science Center, notes the similarities between the alcosynth "secret formula" and e-cigarettes. Like alcosynth, e-cigarettes major marketing pitch is the ability for smokers to maintain a nicotine addiction without being subject to the tragic long-term consequences. Yet the actual long-term knowledge of e-cigarettes' long-term safety is little. On top of this, the tobacco industries have jumped on board, both launching their own e-cigarette brands and promoting "dual use," wherein e-cigarettes are used to cut down on smoking without having to quit. Were alcosynth to gain a significant economic foothold as a legal toxicant, there is no question Big Alcohol would move quickly to use it to augment, not supplant, their product.

Perhaps that could be alcosynth's long-term contribution to the human race: a medicine to ease the transition to sobriety for problem drinkers. To simply throw it onto store shelves, however, is to ignore a century of understanding of how the recreational drug industry works. If we are smart enough to make a hangover-free alcohol, we should be smart enough to understand how it can hurt us just the same.

CT's Automatic Liquor Machines Are a Kid's Best Drinking Buddy

Put a quarter in, get drunk. What could possibly go wrong? On April 12th, the Connecticut State House of Representatives asked that question when they overwhelmingly approved a bill authorizing automated beer and wine dispensers. The devices, which operate off a prepaid card, strip away the face-to-face element of alcohol sales. This interaction provides an important firewall for firewater, both in terms of verifying the patron’s age and in applying bartender’s judgment as to whether the patron can responsibly handle another drink. The machine doesn’t care, as long as there’s money on the card.

Put a quarter in, get drunk. What could possibly go wrong? On April 12th, the Connecticut State House of Representatives asked that question when they overwhelmingly approved a bill authorizing automated beer and wine dispensers. The devices, which operate off a prepaid card, strip away the face-to-face element of alcohol sales. This interaction provides an important firewall for firewater, both in terms of verifying the patron’s age and in applying bartender’s judgment as to whether the patron can responsibly handle another drink. The machine doesn’t care, as long as there’s money on the card.

Worse, this is a slap in the face to one of Connecticut’s lasting contributions to public health. In 1998, the town of Orange, CT, passed an ordnance banning cigarette vending machines in the town. Despite the modest scope of the bill—banning ALL cigarette machines in town meant banning THE cigarette machine in town—the ordnance was challenged in superior court and overturned. The state rallied behind the town, and then-Attorney General Richard Blumenthal got the ban reinstated, clearing the way for local jurisdictions across CT and the U.S. to enact similar bans.

The two central arguments to rejecting the ban have easy parallels in justifications for today’s booze bots. First, lawyers for the vending machine distributor argued that remote locking would allow attendants to verify age. Second, the machines only reflected a small portion of total cigarette sales. But Connecticut State Department of Mental Health surveys at the time showed that 40% of underage smokers bought from the machines, and 6 out of every 10 attempts to use the machines were successful. There is no doubt the unmanned, unmonitored nature of the new automated booze machines make them highly attractive to underage drinkers. And by increasing the rate by which alcohol is distributed in a bar, they absolutely raise the pressure on the servers and bouncers, just begging for them to make a mistake.

These machines also represent a major loss of opportunity to build a new set of safeties in the alcohol market. Responsible Beverage Service (RBS) trainings bolster bartenders’ skills in judging when it becomes unsafe to serve a particular customer, as well as how to de-escalate tense situations and ensure the overall safety of the bar. By increasing the client-load without increasing the number of employees, these machines automatically undermine the ability of a skilled bartender to become a health advocate and look out for their safety and that of their patrons.

Of course, the Connecticut legislature and the makers of the Halcohol 9000 do not need to worry about it. They are far away from the alcohol service. The device encourages the same kind of distance between monitoring and access that put cigarettes in kids’ hands. Moreover, it spits on the triumphs of their predecessors.

SB 384 Supporters Build Their Case on the Backs of the Dead

BREAKING: SB 384 has cleared the Senate GO Committee. READ MORE about the Senate's decision to choose nightlife over all life.

Senator Wiener and the Los Angeles Times use Ghost Ship tragedy to argue for bill, ignorant of California’s own artistic history

The Los Angeles Times sure knows how to make a point: on the backs of the dead. In its coverage of SB 384—the dangerous bill allowing bars to stay open until 4 a.m.—the paper claims the Ghost Ship fire could’ve been prevented had there been a 4 a.m. last call. The 2016 fire, named after the unlicensed living/performance space in which it broke out, killed 36 and was one of the single deadliest building fires in California history. The Times would have you believe it would never had happened if only the kids were drinking at 3 a.m. in some well-financed, well-inspected club. This assertion ignores economics, the cultural history of California, and the role underground venues play in the music scene. More importantly, it cynically exploits the deaths of 36 young Californians to argue for a giveaway to the entertainment lobby that could cost more lives still.

The Los Angeles Times sure knows how to make a point: on the backs of the dead. In its coverage of SB 384—the dangerous bill allowing bars to stay open until 4 a.m.—the paper claims the Ghost Ship fire could’ve been prevented had there been a 4 a.m. last call. The 2016 fire, named after the unlicensed living/performance space in which it broke out, killed 36 and was one of the single deadliest building fires in California history. The Times would have you believe it would never had happened if only the kids were drinking at 3 a.m. in some well-financed, well-inspected club. This assertion ignores economics, the cultural history of California, and the role underground venues play in the music scene. More importantly, it cynically exploits the deaths of 36 young Californians to argue for a giveaway to the entertainment lobby that could cost more lives still.

SB 384 is an on-the-face dangerous bill—it leads to longer public drinking times, more concentrated populations of intoxicated people, and more fatigued and intoxicated driving, along with more subtle vectors for harm—that supporters justify through the short-sighted idea that localities should set their own last-call times. They push past the likely increase in drunk driving, violence, and disruptions to residents with unproven claims of economic benefit (tax revenues would likely be offset if not negated by increased costs to civic services, and largely paid to the state, not the local jurisdiction) and a deeply troubling, disingenuous claim that it would improve public safety.

The Times’s argument hinges on the idea—ascribed to Scott Wiener, the senator that sponsored SB 384—that more nightclubs making more money would allow for more nightclubs total. If there were more nightclubs, Wiener suggests, then promoters would “avoid ad hoc venues like Ghost Ship.”

This claim doesn’t stand up to even the briefest scrutiny. The Ghost Ship fire was not a result of a late-night party. It happened at 11:20 p.m., when every other bar and club in the Bay Area was still open—meaning its attendees were drawn there not by its late hours but by something else. That “something else” comes from unlicensed venues’ ability to book performances that are inherently unprofitable. Even a basic familiarity with economic principles suggests that, unless Wiener and friends intend to flood California with so many new late-night venues that the market is saturated and rents plunge, so long as there are more “mainstream” acts to play large clubs, that’s who will be booked, and the people drawn to more esoteric performers will continue to be forced to seek them at the margins.

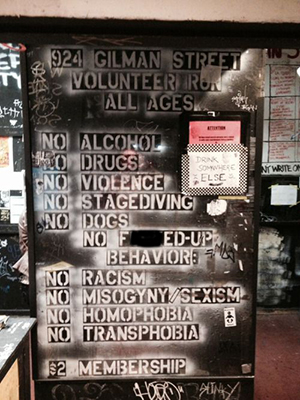

That’s not a new dynamic caused by the rent crisis. The “fashion, music, art” that one DJ tells the Times will be fostered by late last call has always flourished in California. Think about the Beats in San Francisco in the ‘50s, or the Funk Art movement based around Davis and the North Bay in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Those artists changed the face of the culture without needing to tie anything to lucrative entertainment promotions. NPR notes that Los Angeles in the '60s had as strong an art scene as New York—the same New York whose 4 a.m. last call so-called leaders like Wiener argue makes it more appealing than California. Think about the LA sound of hip-hop in the ‘80s through mid ‘90s; spawned as it was through out-of-the-trunk albums sales, those artists thrived despite, not because, of support from mainstream clubs. The Bay Area rock scene in the ‘90s and ‘00s revolved around the explicitly dry, all-ages Gilman St. Project in Berkeley. To claim that California is culturally impoverished because of liquor laws requires either ignorance, amnesia, or an outright contempt for what California has created.

That’s not a new dynamic caused by the rent crisis. The “fashion, music, art” that one DJ tells the Times will be fostered by late last call has always flourished in California. Think about the Beats in San Francisco in the ‘50s, or the Funk Art movement based around Davis and the North Bay in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Those artists changed the face of the culture without needing to tie anything to lucrative entertainment promotions. NPR notes that Los Angeles in the '60s had as strong an art scene as New York—the same New York whose 4 a.m. last call so-called leaders like Wiener argue makes it more appealing than California. Think about the LA sound of hip-hop in the ‘80s through mid ‘90s; spawned as it was through out-of-the-trunk albums sales, those artists thrived despite, not because, of support from mainstream clubs. The Bay Area rock scene in the ‘90s and ‘00s revolved around the explicitly dry, all-ages Gilman St. Project in Berkeley. To claim that California is culturally impoverished because of liquor laws requires either ignorance, amnesia, or an outright contempt for what California has created.

Or perhaps all three. Make no mistake, hucksters like Wiener and the Times aren’t citing precedents or deep familiarity with the Ghost Ship attendees. They are making up stories to justify handing the keys to public health over to massive nightlife operators and Big Alcohol. Judging by the soulless eagerness to build their case on the fresh wounds of real tragedy, they do so without compassion, perspective, veracity, or shame.

TAKE ACTION to oppose this cynical and dangerous bill.

More Articles ...

Help us hold Big Alcohol accountable for the harm its products cause.

| GET ACTION ALERTS AND eNEWS |

STAY CONNECTED    |

CONTACT US 24 Belvedere St. San Rafael, CA 94901 415-456-5692 |

SUPPORT US Terms of Service & Privacy Policy |