In the Doghouse

How Corruption and Cash Led to NIAAA's "Healthy Drinking" Study

- Details

- Published: Friday, April 06 2018 17:35

National Institutes of Health Must Shut It Down Now

National Institutes of Health Must Shut It Down Now

Alcohol Justice is calling for an immediate end to a rigged study on alcohol and health. The Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health Trial (abbreviated MACH15 by its lead investigators) seeks to evaluate the health-promoting effects of alcohol use. It is largely funded with industry money, staffed with industry-approved researchers, and causing government public health watchdogs to turn its back on vital research in the name of appeasing Big Alcohol.

"Healthy drinking" is already a boon to Big Alcohol. Even the slightest hints that alcohol could have a positive effect on health elicit fawning write-ups. These come despite the tenuous nature of the findings. A government-sponsored study reinforcing these findings would be an industry goldmine. Through ready allies at the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the industry may get just that.

NIAAA senior staff, led by demonstrated friend-of-AB-Inbev Dr. George Koob, explicitly solicited over $67 million in funding from the alcohol industry, according to an expose in the March 17, 2018, New York Times. Moreover, follow-up reporting from STAT traced how NIAAA sought to aggressively suppress lines of research that might threaten industry profits.

The NIAAA-led Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health Trial, abbreviated MACH15 by its investigators, is now recruiting. The study seeks to assess the long-term health benefits of "moderate" drinking in 7,800 participants across 4 sites in the U.S., Netherlands, and Nigeria. Each participant will be randomized to either have 1 drink of alcohol per day or abstain from alcohol, for six years.

There are interesting questions that could come from this trial, including: what are the health risks of such low levels of drinking? Do people asked to regularly drink alcohol have any tendency to increase their consumption? Decrease it? The research team, led by Dr. Kenneth Mukamal of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, are not asking those questions. Instead, they are only asking two: how can we prove that alcohol protects against cardiovascular events, and how can we prove that alcohol protects against diabetes?

"There are a lot of great questions about long-term, low-level exposure," said Carson Benowitz-Fredericks, MSPH, Research Manager for Alcohol Justice. "We know it’s carcinogenic at any dose, and that it becomes massively toxic at high doses. But this is so narrow in scope, it makes it seems like they could be fishing for a result."

Both the Times report and the study protocols show that the researchers have zero interest in many of the established harms of alcohol use. They are only looking at three outcomes: cardiovascular disease, pre-diabetes, and/or cognitive decline. In fact, the six-year window of the study makes detection of slow-developing conditions, ncluding cancers and gastrointestinal issues, less likely, even if the trial was set up to monitor those outcomes.

These limitations may not be an oversight, but rather the result of deliberate planning. Dr. Lorraine Gunzerrath, a retired senior adviser to NIAAA, told the times that Dr. Mukamal "already believed that moderate alcohol is a good thing." In fact, having published dozens of papers extolling the benefits of alcohol, his professional reputation depends on it. Speaking to Vox, Dr. Marion Nestle of New York University noted, "If want to know if moderate drinking is good for you, bad for you, or indifferent, you design a study to do that. If you want to prove moderate drinking is good for you, you design a study like [the NIH study]."

In fact, a line in the protocols authored by Dr. Mukamal specifies that the drinks taken by recipients in the drink-a-day group represent "a clinical scenario in which a moderate amount of alcohol is ‘recommended’ by a clinician for potential health benefits."

"No doctor in his right mind would prescribe alcohol for any condition," said Bruce Lee Livingston, Executive Director/CEO of Alcohol Justice, "given that the heart is not the only organ in your body."

This alone is a good reason why he should not be heading up a study with such profound importance to industry. However, Dr. Mukamal had already approached the alcohol industry on behalf of NIAAA with what amounted to a promise to find those results. The study would provide "a unique opportunity to show that moderate alcohol consumption is safe and lowers risk of common diseases," according to a slide that Dr. Mukamal prepared for a series of meetings with the alcohol industry in 2013 and 2014, as reported by the Times. Another slide declared that when asking if alcohol reduces cardiovascular mortality, "we have strong reason to suspect so."

Also speaking to the Times, Dr. Michael Siegel of Boston University noted the study "is not public health research—it’s marketing."

Alongside his efforts to lure Big Alcohol with the prospects of commercially lucrative findings MACH15, Dr. Mukamal gave industry representatives the proposed protocols and the list of potential investigators. This, in effect, allowed the industry to pre-approve every piece of the study before agreeing to fund it. Ceding such privileges to industry funders violates a core tenet of NIH funding: that employees cannot solicit donations, because doing so effectively lets anyone with money dictate the public health agenda.

"The double-dealing here is a betrayal of the public trust," said Livingston. "NIAAA should work for those hurt by alcohol use, not pump up its own standing with the industry."

As Dr. Gunzerrath acknowledges, Dr. Mukamal did not approach the industry of his own accord. The idea to solicit funding from Big Alcohol originated in the highest office of NIAAA, as did the the promise that the trial would be led by an applicant like Dr. Mukamal. Dr. Koob, the director of NIAAA, went further. Not only did he provide assurances to industry about who would conduct "healthy drinking" research, he actively directed resources away from research that might hurt industry bottom lines.

In 2015, Dr. Siegel had been collaborating with Dr. David Jernigan of Johns Hopkins University on a NIAAA-funded study assessing the impacts of alcohol advertising on underage drinking. The two researchers were asked to come to the NIAAA offices to speak about the study. According to STAT, Dr. Koob told the two scientists, "I don’t f***ing care!" about the project’s findings. He then swore not to fund such investigations in the future.

One Dr. Koob and NIAAA leadership’s active efforts to woo industry dollars came to light, STAT obtained NIAAA emails showing that the director had already made the same vow to alcohol industry groups. In a late 2014 email exchange with Dr. Samir Zakhari, a leading executive at the Distilled Spirits Council, Dr. Koob disavowed the study and promised, "This will NOT happen again." At that point, Dr. Mukamal was already making presentations to eager industry representatives.

A follow-up STAT report shows that Dr. Koob made good on his threats to cut off alcohol marketing research studies. Dr. Jernigan had a 2015 grant proposal to NIAAA rejected despite the fact that it received high marks from scientific reviewers. Meanwhile, Dr. Koob told Diane Riibe of the U.S. Alcohol Policy Alliance that NIAAA would not fund "anything on taxes or anything on advertising." While he allowed studies funded under prior leadership to continue under his appointment, the only new grant was actually an extension to a longitudinal study on drinking behaviors in which advertising exposure was only a small part.

"The most generous read is that NIAAA leadership were way too invested in this single research angle," said Mr. Benowitz-Fredericks. "But when you're guiding health policy, you can't have tunnel vision like that. When you do, you can't see the people dying around you."

To end this failure of vision, Alcohol Justice calls upon the National Institutes of Health to immediately suspend MACH15 and return the funds to the industry. It needs to make sure none of its institutes solicit directly from industry funders. And it needs to reassure the public that it is concerned first and foremost with the health of the public.

TAKE ACTION to get NIH to end this biased and corrupt study now.

READ MORE about NIAAA leadership’s cozy relationship to Big Alcohol.

READ MORE about how this study will be used by industry to undermine public health.

READ MORE about Dr. Siegel’s investigations into the NIAAA scandal.

Low-Alcohol Drinks: Emerging From a Cloud of Tobacco Smoke?

- Details

- Published: Monday, March 05 2018 23:24

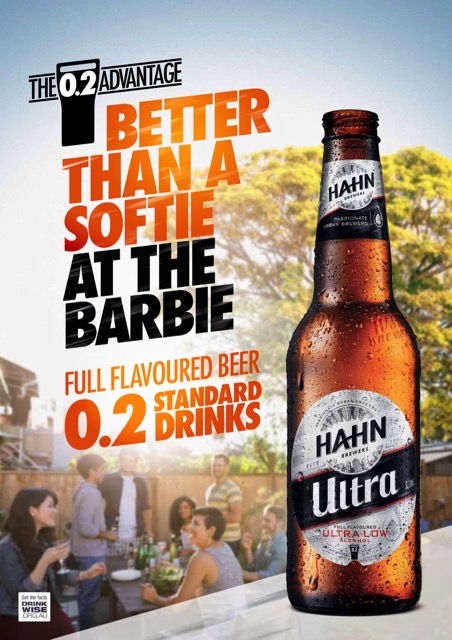

Big Alcohol would like you to know that it’s your friend. It does this in many ways. With advertisements featuring funny skits and catchy phrases. With philanthropic pushes that spend more on marketing than they earn for their recipients. And with grand language about reducing the harm of drinking, often backed by nothing but hot air. Prominent among the ideas floating on that hot air is low-alcohol beverages as a reduced harm product. This forms one pillar of alcohol giant AB InBev’s “Global Smart Drinking Goals.” But growing evidence shows selling low-alcohol products is smarter marketing than it is public health.

Big Alcohol would like you to know that it’s your friend. It does this in many ways. With advertisements featuring funny skits and catchy phrases. With philanthropic pushes that spend more on marketing than they earn for their recipients. And with grand language about reducing the harm of drinking, often backed by nothing but hot air. Prominent among the ideas floating on that hot air is low-alcohol beverages as a reduced harm product. This forms one pillar of alcohol giant AB InBev’s “Global Smart Drinking Goals.” But growing evidence shows selling low-alcohol products is smarter marketing than it is public health.

A Cambridge, UK, research team is trying to bring that concept down to earth. In a new study in BMC Public Health, they reviewed marketing messages surrounding reduced-alcohol beverages. If AB InBev and cohort were determined to replace “normal” alcohol-by-volume (ABV) beverages with their low-alcohol equivalents, then the researchers should have seen language urging consumers to drink these “near beers” and under 9% ABV wines instead of their regular fare. But Big Alcohol is too smart for that.

Instead, these modified products were marketed as being appropriate for every occasion. Often the ad copy urged consumers to drink them during lunchtime, nights in, or while outdoors. In other words, low-ABV drinks were for occasions when normally people would drink no alcohol at all. The authors caution, “they may be being marketed to replace soft drinks rather than alcohol products of regular strength.” In fact, “none of the marketing messages … mentioned drinking less or reducing alcohol harms.”

Other messages centered around health. Reduced alcohol drinks were sold on the basis of lower calories, or greater nutrition, or suitability for athletic events. However, drinking can be a liability for athletes, and alcohol itself is a poison.

“We expect the industry to trot out empty words about health and reducing harm,” said Carson Benowitz-Fredericks, Research Manager of Alcohol Justice. “But the entire concept may be bunk.”

“If we’ve learned anything from tobacco,” he added, “it might actually make harms worse.”

Tobacco industry documents show a successful, decades-long effort to fool consumers into believing that light cigarettes were healthier. In fact, they were designed to be just as addictive as regular cigarettes—and ended up being just as dangerous. More dangerously, the introduction of a “reduced harm” product both assuaged the fears of early smokers and gave inveterate smokers reasons not to quit. While replacing every beer with its low-ABV equivalent will undoubtedly lead someone to drink less alcohol, there is little to no data that this will happen. In fact, a consumer accustomed to a certain level of buzz may just drink twice as many. A consumer accustomed to a certain buzz and convinced they can drink low-ABV products whenever could end up consuming more than they would otherwise. Ubiquitous alcoholic beverages, regardless of the ABV, also twist social norms to make it harder to abstain, and easier for a young adult to start.

These harms may be theoretical, but so are the benefits. AB InBev’s rationale behind low-ABV products derives entirely from a single Health Policy article hypothesizing that reduced-alcohol products could reduce harm. One reference, and that paper itself by warns that “only an independent assessment will be able to identify the effects on harmful drinking.” That is the kind of assessment that never has, and never will, come from Big Alcohol.

READ MORE about the deceptive marketing practices tying alcohol to health.

READ MORE about the shady money behind AB InBev’s Global Smart Drinking Goals.

Alcohol Research Awash in Industry Money

- Details

- Published: Wednesday, January 31 2018 00:01

Even the most careful research can be undone by bias, and history teaches that industry funding does not encourage the most careful research. From the Tobacco Institute to a half a century of sugar industry-fueled misdirection, financial might has repeatedly trumped scientific rigor in health research. Dr. Michael Siegel, Professor of Community Health Sciences at Boston University School of Public Health, is quick to call out the same dynamics with Big Alcohol.

Even the most careful research can be undone by bias, and history teaches that industry funding does not encourage the most careful research. From the Tobacco Institute to a half a century of sugar industry-fueled misdirection, financial might has repeatedly trumped scientific rigor in health research. Dr. Michael Siegel, Professor of Community Health Sciences at Boston University School of Public Health, is quick to call out the same dynamics with Big Alcohol.

Most recently, he has shone light on the International Scientific Forum on Alcohol Research (ISFAR), an invitation-only group of alcohol researchers centered in part at Dr. Siegel’s own BU—and underwritten by the alcohol industry. Dr. Siegel first began looking into ISFAR when they critiqued a landmark meta-analysis that challenged the “j-curve” theory—namely, that people who drink “moderate” amounts of alcohol have better cardiovascular health outcomes than either overconsumers or abstainers. Needless to say, this factoid is a cornerstone of the industry’s campaign to legitimize and encourage daily consumption. Big Alcohol would feel obligated to reject anything undermining “health drinking” messages emphatically, and ISFAR rode into the breach. Conveniently, the organization’s published critique omitted any reference to industry funding for itself and its constituent members.

A growing body of scientific evidence shows that the source of funding can bias research, even when the researchers are ostensibly independent. For this reason, scientific transparency advocates push for disclosure of funding soures. With that in mind, Dr. Siegel revisited the ISFAR controversy to see if they had moved towards open disclosure of industry underwriting.

He found they had, in fact, worked harder to hide them. An ISFAR member was recently forced to correct an academic article for failing to disclose that he was a consultant for the beer industry. Multiple biographies for members either obscure or outright omit industry ties—Dr. Siegel notes a total of 10 members had possible conflicts of interest.

“You want to think that scientists are trying their hardest during difficult times,” said Carson Benowitz-Fredericks, Research Manager for Alcohol Justice. “The excuse is so often, ‘Well, if the industry didn’t fund alcohol research, who would?’ But when you see organizations taking pains to hide financial ties, it makes you realize how quickly that attitude turns into something darker.”

In his piece, Dr. Siegel notes the complicity of his own institution, and calls for ISFAR to be shuttered. “The time to end this scam operation is now,” Dr. Siegel writes. “Especially in a period in which the federal government has basically tossed scientific objectivity out the window.”

“Alcohol Justice is happy to join the choir calling for healthy skepticism,” said Benowitz-Fredericks. “We stand firmly behind Dr. Siegel as he shines a light on this dark corner of drug research.”

READ MORE about Big Alcohol’s deceptive claims of healthy drinking.

More Articles ...

Help us hold Big Alcohol accountable for the harm its products cause.

| GET ACTION ALERTS AND eNEWS |

STAY CONNECTED    |

CONTACT US 24 Belvedere St. San Rafael, CA 94901 415-456-5692 |

SUPPORT US Terms of Service & Privacy Policy |