The Truth Is in the Eye of the Bud Holder

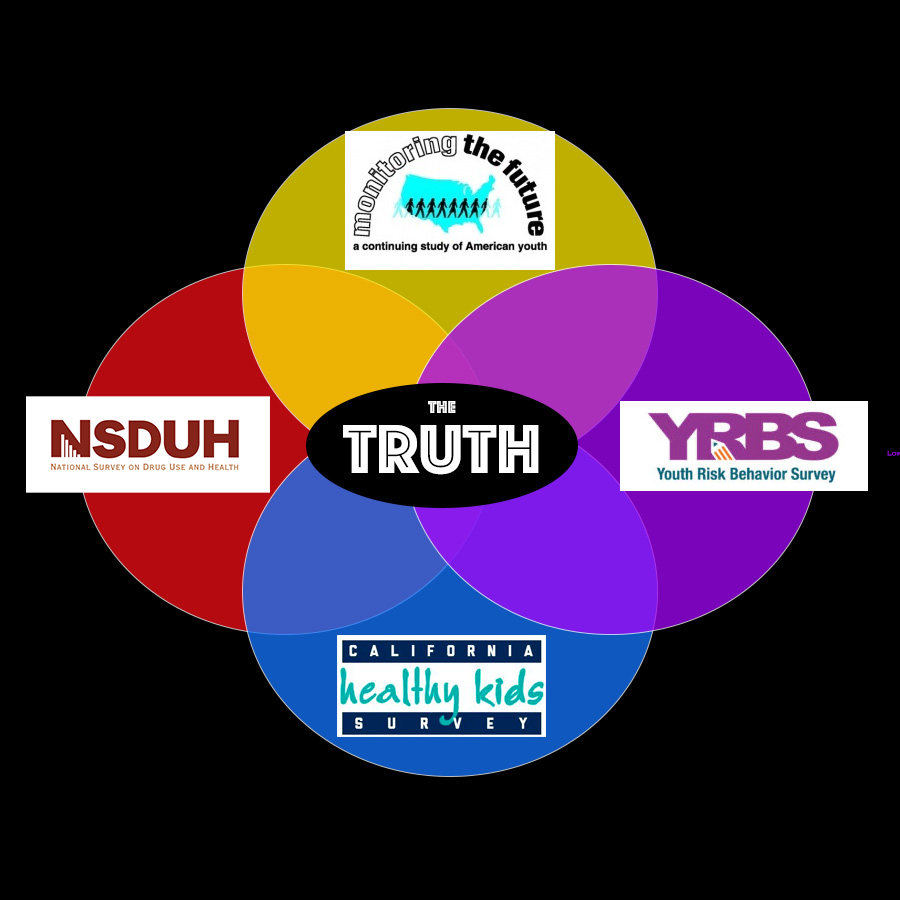

How much underage drinking is really out there? Among high school kids, 0.9% engaged in heavy drinking in 2023. Or was in 2.2%? Maybe just 0.5% did, unless that number is 1% or not known at all. Leaping from survey to survey, the various measurements of youth alcohol use are chaotic, confusing, and sometimes contradictory. For an alcohol harm advocate, it calls forth the question, which of these numbers are the truth? The answer, it turns out, is none of them. Each gives a different view of the truth, and it is up to you to pick which window to look through.

If that sounds needlessly philosophical, well, it is. Each of those numbers were taken from a different major survey. Surveys are meant to take a few answers and expand (or generalize) them to be applicable to far more people. So, the question of “how many kids are drinking alcohol dangerously,” is asked and expanded upon in a different way each time. Below are the most recent numbers of note from three major national surveys, as well as a standard, California-centric one.

How to Choose

Background is included on each survey, to help you pick which one to rely on, but regardless of which one you use, there is an important rule to follow: when comparing use rates for multiple drugs, across multiple age groups, or between genders, sexual identities, and races/ethnicities, be consistent. Use the same survey for each measure. If that survey does not have each measure, then one of the other surveys will—use that one. Similarly, when trying to look at changes from year to year, make sure you are referring back to previous years’ versions of that same survey. Otherwise, you risk not just comparing apples to oranges, but comparing apples looked at through a microscope to oranges measured with a thermometer.

This article only calls out the current (2023) alcohol measures,. However, trends can always be obtained by looking back at previous years’ surveys. Each survey contains dozens if not hundreds of additional, important questions on not just alcohol but the overall health of the youth interviewed, which are available in the linked report for each survey. Similarly, the expanded data tables for these surveys usually offer breakdowns by gender identity and race/ethnicity, and often by sexual identity; some also break up data by geography.

If you are having trouble finding these more specific breakouts, we have identified the agency which oversees the report—all of these agencies are public. That means they exist to serve all residents of the United States—including you. With that in mind, nearly every public research agency has help desk professionals willing to walk constituents through the data. Often, they can quickly point you to the document or file you need—at times, even if it is not yet public. When in doubt, ask.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

2023 Results:

Any alcohol use, past 30 days, 12-17 years: 6.9%

Any alcohol use, past 30 days, 18-25 years: 49.6%

Binge alcohol use, past 30 days, 12-17 years: 3.9%

Binge alcohol use, past 30 days, 18-25 years: 28.7%

Heavy alcohol use, past 30 days, 12-17 years: 0.5%

Heavy alcohol use, past 30 days, 18-25 years: 6.9%

The most recent report can be accessed here.

Full data tables, including measures not covered the report, are available here.

The NSDUH—usually pronounced “niz-duh”—is coordinated by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). SAMHSA’s principle interest is in coordinated treatment services, so the NSDUH sample can include all U.S. residents, 12 years old and older. Because of the wide scope, NSDUH tends to report in slightly inconvenient age brackets. The younger group, 12 to 17 years old, bridges both junior high and high school ages. The older, 18-25, not only lumps some high school students and post-college adults, but straddles the line of legal alcohol purchases.

In exchange for this blunt imprecision, NSDUH gives a better ability to put youth drinking behaviors in the broad context of everyone’s. It also includes a number of questions centered around diagnostic criteria and use of services that are not covered in the other major national surveys.

NSDUH’s most significant strength, however, derives from where the surveys are administered. Unlike the rest of the surveys mentioned in this article, it is conducted at home, face-to-face with the respondents. This ends up being a double-edged sword. The downside is that underaged participants may be accompanied in the interview by a parent or caregiver. This risks making kids reluctant to speak openly about a range of experiences, including drug use. On the other hand, the other surveys are school-based, meaning kids subject to truancy, home-schooling, and dropping out cannot be reached. Similarly, school-based surveys cannot capture drinking behavior changes between the school year and summer or other breaks, while NSDUH can, and actually accounts for in how the reports weight responses.

Monitoring the Future (MTF)

2023 Results:

Alcohol use, lifetime, 10th grade: 35.8%

Alcohol use, lifetime, 12th grade: 52.8%

Alcohol use, past year, 10th grade: 30.6%

Alcohol use, past year, 12th grade: 45.7%

Alcohol use, last 30 days, 10th grade: 13.7%

Alcohol use, last 30 days, 12th grade: 24.3%

Daily alcohol use, 10th grade: 0.4%

Daily alcohol use, 12th grade: 0.9%

5+ drinks in a row, last 2 weeks, 10th grade: 5.4%

5+ drinks in a row, last 2 weeks, 12th grade: 10.2%

10+ drinks in a row, last 2 weeks, 10th grade: 2.1%

10+ drinks in a row, last 2 weeks, 12th grade: 2.2%

The most recent report can be accessed here.

Arguably the flagship youth substance use survey, MTF, administered by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, has been administered consistently since 1975, providing generational data in substance use trends. Rather than cover large age groups, it divides its respondents into 8th graders, 10th graders, 12th graders, college students, and young adults. This makes MTF data not just a snapshot of adolescent use right, but, as NIDA explains, of “developmental changes that show up consistently for all panels (“age effects”) … Consistent differences among class cohorts through the life cycle (“cohort effects”) … and changes linked to different types of environments (high school, college, employment) or role transitions (leaving the parental home, marriage, parenthood, etc.).”

The questions, especially around alcohol, are highly specific. Alcohol responses go well beyond the ones listed above, and include other kinds of drinking patterns, preferences in product category, and engagement with “stupid products” such as alcopops or powdered alcohol.

The flip side is that, like NSDUH, the college-age and young-adult groupings, or “cohorts,” are really only intended to provide context for the much more specific secondary school cohorts. The groupings again assume that 18-year-old college students have analogous behaviors to 22-year-old ones. There are situations where this simply does not do justice to the risks. For instance, as the California legislature moves more and more aggressively to open the doors for Big Alcohol targeting college students, it becomes important to disaggregate those data and see what changes as young adults cross the threshold of being able to purchase alcohol legally. The survey materials also acknowledge that MTF misses students who dropped out of secondary education, amounting to approximately 5% of high school-aged students.

However, for assessing national and decades-long trends, MTF offers an unparalleled snapshot of trajectories for the nation’s youth.

Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)

2023 Results:

Alcohol use, past 30 days, high school students: 22%

Alcohol use, past 30 days, high school students, female: 24%

Alcohol use, past 30 days, high school students, male: 20%

The most recent report can be accessed here.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) run their own regular survey, YRBS, which in turn feeds into their Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. YRBS’s alcohol measures are considerably impoverished compared to the other surveys in this roundup, though it should be noted that it has been slower to update with 2023, which should eventually reflect a fuller range of measures. And like MTF, it is an in-classroom survey, meaning there is a small but significant swath of youth who never get the chance to answer it.

What YRBS lacks in depth, it makes up in breadth. YRBS data encompass not just substance use and diagnostic questions, but questions about sexual risk behaviors, suicidality and mental health, diet and exercise, and other major determinants of wellbeing.

In addition, YRBS’s measures are keyed to Healthy People 2030, a cyclically updated roadmap to reduce preventable morbidity and mortality across multiple risk areas. By digging into youth risk behaviors in depth and tying them to a public, widely accepted set of goals, YRBS better describes the way one risk behavior can become interwoven with many others. In addition, while all of the surveys have some ability to disaggregate data by demographic or region, YRBS builds the ability to identify racial/ethnic, gender, tribal, and geographic disparities into its design.

California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS)

2023 Results:

Alcohol use, lifetime, 9th graders: 16.3%

Alcohol use, lifetime, 11th graders: 30.3%

Ever very drunk or sick after drinking, 9th graders: 6.8%

Ever very drunk or sick after drinking, 11th graders: 15.7%

Alcohol use, last 30 days, 9th graders: 6.5%

Alcohol use, last 30 days, 11th graders: 13.7%

Binge drinking, last 30 days, 9th graders: 2.8%

Binge drinking, last 30 days, 11th graders: 7.3%

The most recent report can be accessed here.

County and school district reports can be accessed here.

CHKS, overseen by the California Department of Education, is the go-to for a great deal of California-specific alcohol and drug use information. Aside from the biennial statewide report, CHKS provides data on county and school district levels. However, it is slow to update, and its results were greatly upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. As such there is no 2022-2023 biennial report, and only some of the 2022-2023 district reports have been released.

CHKS data is obtained from in-classroom surveys, leaving it vulnerable to the same deficiencies as other school-sampling surveys that miss students being homeschooled or not enrolled in secondary education. Because the surveys are administered on a rolling basis, they are not able to capture year-to-year trends. Although the main alcohol use questions are consistent year over year, there are ancillary questions that are sometimes dropped or replaced between years.

Unlike other surveys, CHKS is divided into much narrow age ranges: 7th grade, 9th grade, and 11th grade. The biennial frame of the survey potentially makes it possible to use multiple biennial reports to make assertions about cohorts as they move through middle and high school. Until some of the concerns around the haphazard administration of the survey are fixed, however, this is not recommended.

So Which One Is Right?

All of them are. Each one has limitations, and sacrifices some answers in order to better answer others. For seeing what other behaviors alcohol use is associated with, YRBS may be strongest; for year-by-year trends in alcohol consumption, MTF seems to be the best. CHKS was designed specifically to serve local California assessment needs, but lacks the resources of the federal government behind it. NSDUH focuses more intensely on risky alcohol use as a medical condition, not just a behavior.

The real truth is not the one in the survey—it’s the one in the respondent. The kids themselves, the kids you interact with and want to help, are the ones whose lives are not a bubbled scantron, but an unfinished map. Try to choose the set of questions and answers that best helps them fill it in.

— Carson Benowitz-Fredericks, MSPH

READ MORE about the challenges in comparing different youth surveys.

READ MORE about how youth can control their futures by reclaiming retail.