In the Doghouse

The Corporate Cynicism Behind "Responsibility Month"

You might not have noticed there's a quiet a battle for April. Not a battle fought on that day, nor for a person named April. The month of April. On one side are advocates for public health and lives that do not end in preventable deaths. On the other are the Big Alcohol corporations that benefit from the status quo. The battleground is something as simple, as stupid, and yet as powerful as a word.

You might not have noticed there's a quiet a battle for April. Not a battle fought on that day, nor for a person named April. The month of April. On one side are advocates for public health and lives that do not end in preventable deaths. On the other are the Big Alcohol corporations that benefit from the status quo. The battleground is something as simple, as stupid, and yet as powerful as a word."Responsibility."

This year, the organization Responsibility.org introduced a social media campaign titled "April is Responsibility Month". The campaign was specifically hinged on taking April's established Alcohol Awareness Month and replacing it with the concept of responsibility (with a hashtag). Their explanation relies on very assertive and utterly misleading language.

Awareness is important – how is one to eliminate an issue like drunk driving or underage drinking if one isn’t aware of the facts surrounding that issue or the effective strategies to implement in order to create change?

Yes, “awareness” is a crucial step in the fight against drunk driving and underage drinking. But, it is only the first step.

Equally critical -- if not more so -- is “responsibility.” If each organization and person – parent, teacher, college student, law enforcement official, judge, prosecutor, industry employee, and so on – were to take ownership and responsibility for eliminating these issues, drunk driving and underage drinking would decline at an even more rapid rate than they have over the last two decades (which is a lot, btw).

As it is currently carried out, April's Alcohol Awareness Month serves as a platform for organizations all over the government, health, and advocacy sectors to launch their own campaigns. These disparate campaigns each highlight the various needs to cut down on the ever-rising tide of alcohol mortality. This mortality derives from all sorts of proximal causes: violence, motor vehicle crashes, alcohol poisonings, overdoses primed by combining drugs and alcohol, agonizing deaths from liver failure and cancer, heart disease and neurodegeneration, and many more. The distal cause, though, remains the same: alcohol overconsumption.

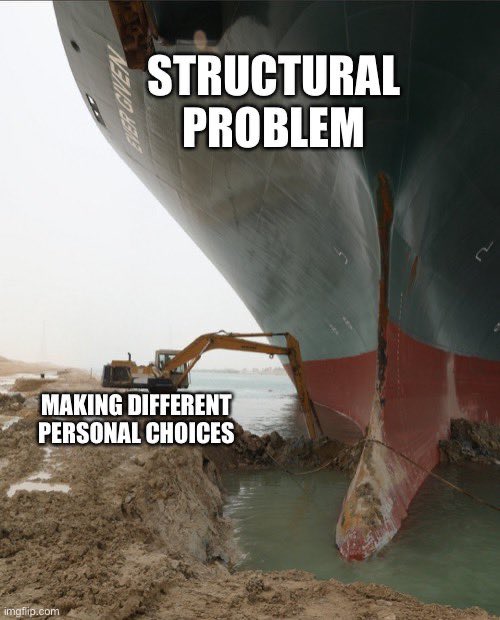

By narrowing the spotlight to only shine on dangerous driving and underage use, Responsibility.org hides many, many deaths and injuries associated with alcohol. By claiming the central concern is "responsibility," the organization makes it seem like the problem is individuals. According to this framing, structural reforms do not exist and that producers could not possibly be expected to operate differently. The particular framing for "Responsibility Month" is even more cruelly misleading, as while underage drinking has been declining, the "rapid" rate was a product of the pandemic-related lockdowns. (In fact, last year, most measures of youth drinking went up compared to 2021.) The irony of including industry employees as a group that should be more "responsible" while not taking the responsibility for their own sloppy and misleading language is likely not lost on the authors of this campaign.

Because, it turns out, the authors of this campaign are for all intents and purposes industry employees.

Because, it turns out, the authors of this campaign are for all intents and purposes industry employees.Responsibility.org is underwritten by a true rogue's gallery of Big Alcohol. Multinational megadistiller (and tireless opponent to any governmental health-related campaigns) Diageo heads up the list, with Bacardi and the binge-centered Jagermeister behind them. Most notable to Alcohol Justice supporters would be Constellation Brands, whose Mexico-based breweries have helped bleed the ground dry and who joined Responsbility.org only in 2022, after the Mexicali Resiste movement exposed their devastation and ground their construction efforts to a halt. But even smaller producers understand the value of preventing any serious action. Over 120 craft producers support the effort, including the Bay Area's 21st Amendment, and Buzz Ballz, whose high-alcohol content, heavily flavored, quirkily packaged, and sophomorically named offerings are probably the epitome of a youth-focused product.

The reach does not even end there, however. Aside from the Big- and Would-Be-Big Alcohol sponsors, Responsbility.org receives funding from all sorts of organizations interested in alcohol deregulation. Prominent among these is Amazon, whose bottomless appetite for monopoly has already lead to them planning a wide-set effort to destroy public health-oriented alcohol restrictions. Joining them are delivery companies Grubhub, Uber, and notorious tip-stealers Doordash--all groups that would like to make anytime, anywhere alcohol the law of the land, leaving "responsibility" the only remaining brake against harm. Lastly, as legalization continues, the cannabis companies GoPuff and Canopy have declared a vested interest in a world where the harm from substance use can only ever be the fault of the person experiencing it. (And Constellation also owns a major stake in Canopy, making it even clearer how corporate interests are aligning.)

Despite these many moneyed groups' claims to be reconceiving alcohol harm prevention, their favored tactic--to blame individuals--will likely struggle in growing. Not because we are too savvy, but because in the U.S., the public response has always been to reflexively blame people experiencing substance use issues. But true change, moving closer to an environment that is truly protective against alcohol-related death, harm, and misery, requires a big lift. The United States needs bold ideas like effective health labelling, alcohol ad-free public spaces, ABV-pegged excise taxes, and charge-for-harm tax and fee strategies have to be backed up by time-tested approaches such as retail availability limits, lower BAC thresholds for ticketing, and increased availability of alcohol-free youth activities. Those cannot be put forward through individual responsibility, only through collective pressure and care. And Big Alcohol should be held responsible for its cruel and deep-pocketed efforts to deny that.

Sign image by Nosha via Flickr, used under Creative Commons license.

Budweiser Pays for World Cup Workers' Graves

This November's World Cup tournament features an unusual wrinkle--attendees risk jail time for enjoying one of its most prominent sponsor's products. Because Qatar, the event's host country, follows Islamic prohibition against alcohol, anyone partaking of sponsor Budweiser's signature products risks up to six months in prison, according to the New York Daily News.

This November's World Cup tournament features an unusual wrinkle--attendees risk jail time for enjoying one of its most prominent sponsor's products. Because Qatar, the event's host country, follows Islamic prohibition against alcohol, anyone partaking of sponsor Budweiser's signature products risks up to six months in prison, according to the New York Daily News.But as Big Alcohol has done time after time, Budweiser has wrenched Qatari law to fill its own pockets. The World Cup events will have "fan zones" set aside from alcohol consumption. This exemption is not new. Writing for Defector, Charles Pierce reminisces about the 1993 World Cup qualifiers in Qatar:

[Foreign contracting] required Qatar to make some allowance for the Americans who came to town to work the oilfields. ... In this case, as in so many others, expedience trumped religious doctrine.

And that plays into the real horror of Budweiser's engagement. Qatar's reliance on migrant labor for its construction projects is well-recognized. The enormous scope of the World Cup facility and attendant infrastructure may cost Qatar upwards of $220 billion. This far-reaching campaign has been underwritten in no small part by its sponsors, including Adidas, Coca-Cola... and Annheuser-Busch InBev, the owner of Budweiser.

That money has gone into a development scheme that, according to Guardian estimates, cost 6,500 lives. According to an Amnesty International report, the businesses practices that Budweiser helped pay for have been egregious: South Asian laborers from Bangladesh, India, and Nepal asked to take on $500 to $4000 in debt for the "recruitment fees," then shipped to Qatar with the debt still standing. On arrival, the laborers' passports were confiscated.

The conditions of essentially indenture were just the beginning. Salaries were substantially less than promised. Payments were delayed. Residence permits were allowed to expire, making laborers at risk of jail if they leave the work camp. Living conditions are cramped--eight or more to a room--and work conditions dangerous; the Guardian reports that heat death was also a persistent risk for laborers.

Budweiser has been involved in World Cup sponsorship for over a decade. While the terms of their contract are not public, estimates have them paying between $130 and $325 million during the lead-up, with a data-mining-heavy ad campaign launched at the end of 2022. This steady involvement even as the details of tragedy mount has not gone unnoticed. In September, Human Rights Watch called for a sponsor pressure campaign towards the Qatari government. In a culture-jamming campaign aimed at the World Cup sponsors, an activist graphic designer augmented the Budweiser (the King of Beers) logo with the slogan "you can't be the kind without slaves."

AB InBev has acknowledged the situation in Qatar, agreeing to join Human Rights Watch's call for better compensation for migrant workers and issuing--at the very end of a March 2022 press release--a statement of support for the laborers. Yet, at the same time, they have not acknowledged the stories of widespread abuse and mortality detailed by Amnesty International and the Guardian. They did, however, launch an ambitious, multiplatform World Cup ad campaign themed--and no, we're not making this up--"The World Is Yours to Take."

Alcohol Justice has long raised the call to Free Our Sports. Yet this is an instance where the conjunction of sports, alcohol, and money lead to underwriting violations of human liberty that shock the conscience. In its ceaseless, remorseless campaign to get its product in front of sports fans (including underage ones) across the world, Budweiser has fed a brutal labor machine that will stain soccer for decades. There won't be a trace of red on Budweiser's balance sheets, though.

READ MORE about Free Our Sports.

READ MORE about AB InBev's cynicism in the face of tragedy.

I'd Like to Give the World a Drinking Problem

The realm of Big Alcohol just welcomed a friendly, red-and-white face. The Coca-Cola company, the second largest beverage company in the world, has been quietly rolling out a series of alcoholic beverages over the past three years, making it a sudden but formidable force in alcoholc sales. These new products—including alcoholic Simply "juice," alcoholic Topo Chico seltzer, and a spiked Fresca soda—all take cues from the worst trends in flavored malt beverage production. All three are cross-branded with familiar, non-alcoholic products. All three hide under the veneer of "healthy" alcohol. And all three are the kinds of flavor-masked products that frequently serve as the drink of choice for youth who still dislike the taste of alcohol.

The realm of Big Alcohol just welcomed a friendly, red-and-white face. The Coca-Cola company, the second largest beverage company in the world, has been quietly rolling out a series of alcoholic beverages over the past three years, making it a sudden but formidable force in alcoholc sales. These new products—including alcoholic Simply "juice," alcoholic Topo Chico seltzer, and a spiked Fresca soda—all take cues from the worst trends in flavored malt beverage production. All three are cross-branded with familiar, non-alcoholic products. All three hide under the veneer of "healthy" alcohol. And all three are the kinds of flavor-masked products that frequently serve as the drink of choice for youth who still dislike the taste of alcohol.

The initial entry, back in 2020, was alcoholic Topo Chico. Nominally a seltzer produced in Monterrey, Mexico, the alcoholic version keeps the brand but takes the production back into the United States. Yet the branding remains: a New York Times article called out Coca-Cola's appeal to "perceived Mexicanness" in its promotion of the brand. While the dreary colonialism inherent in exoticizing an everyday Mexican brand is obvious, the potential to target Latinx communities may be even more threatening. Despite a history of drinking less than non-Latinx White U.S. residents, recent surges in alcohol use disorder are driven in part by a rapid increase in risky alcohol use in Latinx communities.

In the past year, Coca-Cola has branched out further. Fresca, a sugar-free soda often marketed as a "healthy" alternative to soda, is now being used to brand a cocktail-in-a-can. These kids of "ready to drink" cocktails combine often high ABV, strong flavor, and a packaging—a can—that suggests they should be consumed in one sitting. These are, for all intents and purposes, alcopops, and like alcopops, they draw more than their share of underage drinkers. And like Topo Chico, the Fresca brand is associated with health, and very specifically with being low-calorie. Unlike Topo Chico, however, Fresca has historically been targeted at women. So with alcoholic Fresca, Coca-Cola has managed to prime teen girls for both an alcohol use disorder and an eating disorder.

But why should the beverage behemoth stop with teens? Why not... juice? Among the many brands in its portfolio is Simply, a juice brand that is branded with the assertion that it is free of any additives besides juice. (This claim, while true, is deceptive, as very few juice brands currently on the market have anything other than juice, and prepackaged juice is, itself, a sugary beverage just like soda.) The same lemonade, then, that parents pour for their children will now be sold as a 24 oz. alcoholic tallboy. What a perfect procession to sear alcohol into developing minds: get them to recognize booze brands young, get them hooked when they're teens, and keep them drinking "healthy" "seltzers" when they start to worry about mortality.

The irony is, Coca-Cola faces little risk from brand dilution. Already, sugary beverages form the backbone of its $286 billion global empire. These beverages are complicit in a wide swath of health harms, including, according to Nature, "weight gain, ... type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and some cancers." Yet Coca-Cola has been nearly immune from regulation, going so far as to join with Anheuser-Busch InBev to threaten a budget-crippling ballot measure unless California blocked soda taxes. They have the economic strength and the political ruthlessness to push these new, alcoholic products into any hand they see. Based on the rapid expansion of their product lines, these are only the tip of an iceberg. If that spurs an anxious sensation of looming threat, well, Coca-Cola themselves have long urged customers to "Taste the Feeling."

READ MORE about the alcopop gateway to youth use.

READ MORE about the great "healthy drinking" hoax.

More Articles ...

Help us hold Big Alcohol accountable for the harm its products cause.

| GET ACTION ALERTS AND eNEWS |

STAY CONNECTED    |

CONTACT US 24 Belvedere St. San Rafael, CA 94901 415-456-5692 |

SUPPORT US Terms of Service & Privacy Policy |